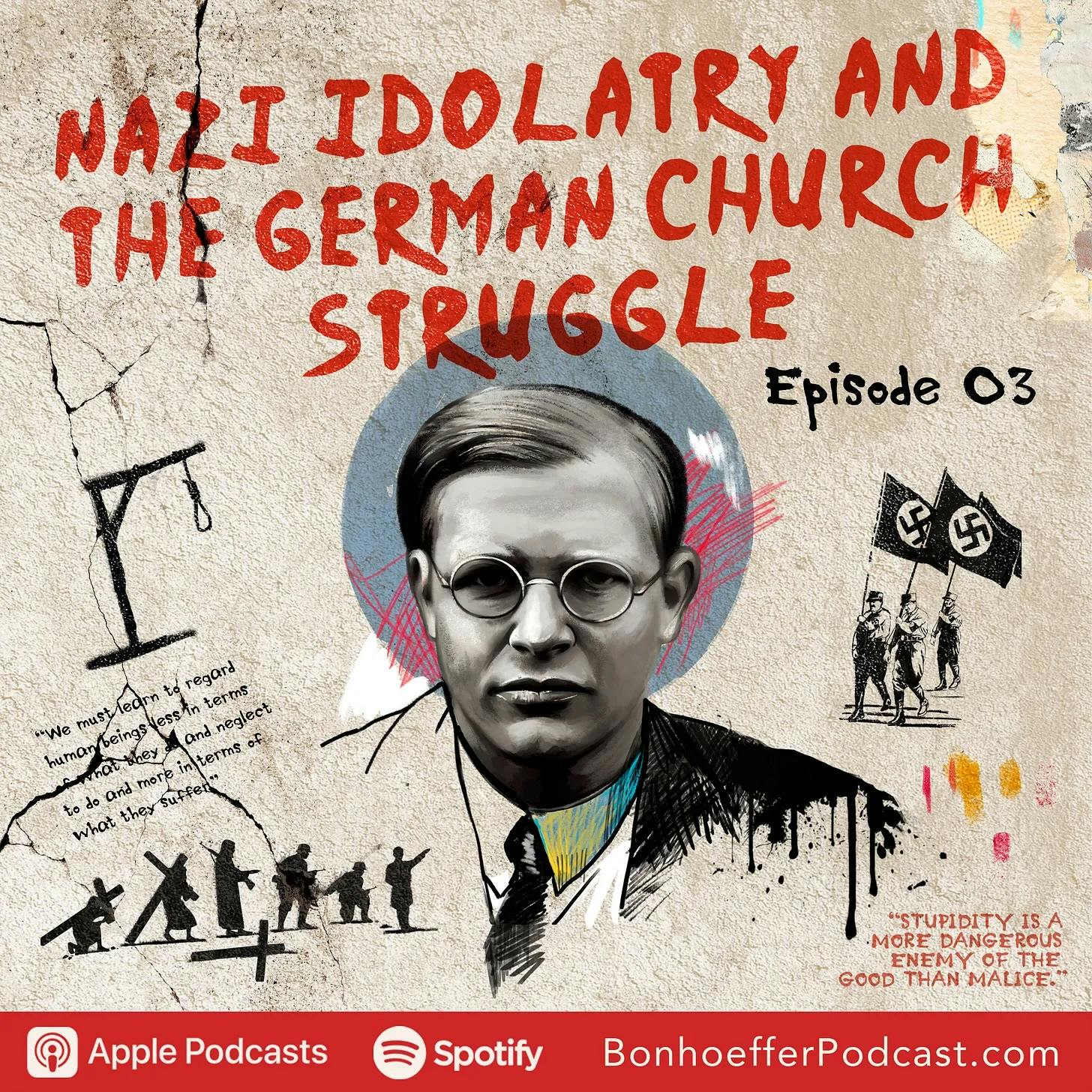

Nazi Idolatry & the German Church Struggle

This episode of The Rise of Bonhoeffer explores Dietrich Bonhoeffer's experiences after returning to Germany. Transformed by his time in New York City, he visits the theologian who first awakened the conscience of the German church to the rising totalitarian idolatry - Karl Barth. The episode tracks his burgeoning role in the German church struggle from his initial involvement in the ecumenical movement, his time as a youth minister to the working class of Berlin, and his entrance into the academic classroom. After Hitler is sworn in as Chancellor and the rapid Nazification of Germany begins, Bonhoeffer comes to see the deep discipleship needed to resist the spreading German Christian Faith Movement. As Germany falls deeper into chaos, Bonhoeffer navigates the shifting political landscape, establishing international connections that later prove crucial during his resistance against the Nazi regime.

Follow the Rise of Bonhoeffer podcast here.

Spend a week with Tripp & Andrew Root in Bonhoeffer's House in Berlin this June as part of the Rise of Bonhoeffer Travel Learning Experience. INFO & DETAILS HERE

Want to learn more about Bonhoeffer? Join our open online companion class, The Rise of Bonhoeffer, and get access to full interviews from the Bonhoeffer scholars, participate in deep-dive sessions with Tripp and Jeff, unpack curated readings from Bonhoeffer, send in your questions, and join the online community of fellow Bonhoeffer learners. The class is donation-based, including 0. You can get more info here.

Featured Scholars in the Episode include:

Victoria J. Barnett served from 2004-2014 as one of the general editors of the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, the English translation series of Bonhoeffer's complete works. She has lectured and written extensively about the Holocaust, particularly about the role of the German churches. In 2004 she began directing the Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum until her retirement.

Andrew Root is Carrie Olson Baalson Professor of Youth and Family Ministry at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is the author of more than twenty books, including Bonhoeffer as Youth Worker: A Theological Vision for Discipleship and Life Together, Faith Formation in a Secular Age, The Pastor in a Secular Age, The Congregation in a Secular Age, Churches and the Crisis of Decline, The Church after Innovation, and The End of Youth Ministry? He is a frequent speaker and hosts the popular and influential When Church Stops Working podcast.

W. Travis McMaken, PhD, is the Butler Bible Endowed Professor of Religion and Associate Dean of Arts and Humanities at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, MO. He is a Ruling Elder in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). McMaken’s writing engages primarily with 20th century theology (esp. Protestant theology, with specialization in Karl Barth, Helmut Gollwitzer, and T. F. Torrance) while working constructively on the subjects of sacramentology, ecclesiology, and political theology. Check out his recently edited book Karl Barth: Spiritual Writings.

This podcast is a Homebrewed Christianity production. Follow the Homebrewed Christianity and Theology Nerd Throwdown podcasts for more theological goodness for your earbuds. Join over 70,000 other people by joining our Substack - Process This! Get instant access to over 45 classes at www.TheologyClass.com

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Bonhoeffer's Return: Awakening to Crisis and Discipleship

Paul von Hindenburg is president of Germany in 1931

- Germany has been ruled by the aging, single minded old warrior field marshal Paul von Hindenburg. Honored as the symbol of glory's past, he is 84 and fast slipping into senility as president. However, he is the only man who can keep Germany from being splintered by political strife. Few men ever held a position so vital, no man ever wanted it less. As prosperity returns to Germany, a small political party in Munich, born in the wake of the war, struggles to survive. Its slogan is Germany awake with armed revolution. It's avowed aim, it attracts its members from the political lunatic fringe called nazis. They are led by a one time vagrant painter named Adolf Hitler.

Tripp: Episode three of the rise of Bonhoeffer is back

Hello, everyone. This is Tripp. And we are back for episode three of the rise of Bonhoeffer.

Tripp, good to be with you again.

We're picking up the story with Dietrich returning from his time in New York, having had a number of different powerful experiences, he awakened to the invitation of deep discipleship and the sermon on the mount. He saw the limits of a very nationalist form of faith. And the kind of solidarity you saw in Jesus on the cross is one that the church is called to today. And these transitions are moving through him as he shows back up in Germany.

For those of you who have been on this journey with us for the last two sessions, you'll remember that when Bonhoeffer is getting ready to leave, he is not unaware of what is happening in Germany. His friend has written him a letter telling him about the rising anti semitism, the unrest, not just in the streets of Germany, but also out in the rural areas. When Bonhoeffer returns, he's not exactly un alert to what is going to happen to him as far as going into a troubled social situation. But the minute that he gets back, one of the first things that he does is he decides he's going to make his way to the great man of Switzerland, Karl Barth's seminar. Barth had taken a chair in reformed theology at the University of Bonn, and Bonhoeffer was interested in meeting, meeting him, meeting the person that had engaged him over theological issues in his second dissertation and through the twenties.

And one of the things that is hard to communicate if someone just doesn't happen to be a theology nerd, you know, and everyone isn't one is just how influential Karl Barth is for 20th century theology. Now, Jeff, you wrote a dissertation on him, so that means you've spent more time with Carl than a lot of people have. When you think of the kind of, power that Karl Barth communicated enough to attract Bonhoeffer here to go visit him, and for theologians since then to keep wrestling with him. What is it that people may not know, hearing the name that a, theology nerd goes? Carl?

Well, let's pull the lens back. And also for those of you who have not been exposed to that name before, it's b a r t h. Let's enter it into this. Barth had the same kind of theological education as Bonhoeffer. He had gone to german schools. He had studied under von Harnack. He had studied under Wilhelm Hermann. He had studied under some of the finest of the protestant, theologians. He was enamored with Friedrich Schleiermacher early in his academic career. But when he went back to Switzerland and he had to start serving time in the parish, certain realities and things started to kind of bump up against a kind of academic theology. What's profoundly compelling in some ways is that it is real life situations on the ground that actually change both Barth and Bonhoeffer.

Most Germans dismiss the Nazis as a comic band of toy soldiers, particularly after they stage an abortive uprising. But the debacle has taught Hitler, that he must find another way to power. the nazi party begins a quest for respectability and members. In four years, Hitler will recruit more than 100 mainly discontented veterans of World War one.

One of the ways that Barth was changing is that he became increasingly dissatisfied with a theological perspective that made an inherent, assumed connection between the world that he was living in and God's order or God's will. And this began to disturb him a little bit, especially when he saw something like the 93 german intellectuals, some of whom were his teachers, von Harnack and other people, other teachers that he had admired and respected. And they actually signed on to Kaiser Wilhelm's war manifesto in the beginning of World War one. And this was profoundly disillusioning. He sees this as a betrayal of his entire theological education. And in that sense, he's kind of on a path now to say, what are we talking about when we're talking about goddess mhm? Are we just talking about the human in a louder voice? He is influenced by critiques from people like Ludwig Feuerbach and Hope, Franz Overbeck, and others who were raising significant questions about whether or not protestant liberal theology had ended up creating a God in its own image.

Yeah. And I think theologically the category he appropriates that makes so many of the kind of stewards of religious nationalism in Europe uncomfortable is idolatry as a reform theologian. Karl Bart, in the legacy of John Calvin recognizes that human beings are idol factories. We're really good at, ah, taking our own convictions, our own systems, our institutions, our habits, our patterns, calling them natural, underlining them with a divine pen, and going, this is just how God made it. And that revelation that the very people who were inviting you into the christian tradition, trying to help you understand it, and being able to articulate the faith in a way, are also unable to distinguish their commitment to the God who died cross dead and the one calling them to war.

And so Bonhoeffer and Barth are very concerned about this assumed, inherent constituent connection between culture and faith. The way it plays out for Barth is in some ways different. He's entered into this path earlier, which gives rise to the kind of crisis theology that Bonhoeffer is looking into in the 1920s. But in the 19 teens, Barthes is already on the move toward particular theology of crisis. And he is increasingly suspicious of a theology that takes God and wraps God into the national flag, shoves a weapon into God's hand, and says, my enemy is your enemy.

Travis McMakin, professor of religion and associate dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at Linwood University and author of Karl Bart the spiritual writings, has a little something to share on this.

Barth was battling the same situation. It's what he started with in the context of World War one, when he saw that all of german culture, including german theology and Christianity up to that point, fell in line behind the german war effort. In World War one, the idea that german cultural superiority required the seizure of additional territory, especially colonial territory, was one of the big end, goals. It's what he battled all through the late twenties and into the thirties as the Weimar Republic began to fracture and very reactionary forces of different kinds emerged. It's what motivated his rejection of natural theology, because people took very seriously the idea that the father land and nate and blood and folk were not only intellectual concepts, but moral values.

So Bart's in a dilemma now. He's trying to figure out what he's going to do when he feels so alienated from his culture, from his world. And he's trying to work this out even as he's pastoring a parish in Soffanville in Switzerland.

Travis McMakin: Barth was influenced by socialist thinking early on

Once again, we turn to Travis McMakin M to, share with us a little bit about Barthes life in the parish and the changes that he was undergoing at this time from his early.

Days as a pastor in Saffenville in Switzerland. There are textile factories there, factory workers and the owners are in his congregation and he is preaching about the evils of capitalism, and he is organizing with the workers. He is putting on classes for them to help them raise their educational level and be able to function more intentionally in society. He's invited to run for office as a part of the swiss socialist party. All of that is right there. At the same time that he is also doing his theological critique and getting that off the ground. To say, on this theological side, people are taking for granted things that they should not be taken for granted. They're thinking that God can be found embedded in the world in a way that Barth doesn't think you can find God embedded in the world. And Barth wants to say that when God does show up, God shows up on God's terms, and God criticizes where in the moment of action, in the moment of call, we have to encounter not only what we are invited to do positively, but to also realize the way that things have gone wrong to bring us to this point, to require that kind of action.

Barth was influenced in this move to a kind of socialist perspective by other theologians, other teachers that he had. But in the end, one of the most disappointing things is that this politics, too, ended up betraying Bart all through that.

He's looking for a conceptuality to prevent what happened in Germany around world War one, which was, you had a strong socialist political party who rolled over and went, along with a vote in the Reichstag to not be critical of the government for the duration of the war, because german national success, german colonial interests, all of these things were more important than debate. That was one of two betrayals that I think Barthes took really, really hard. His theological teachers signed on to support the war. That was one betrayal. The church, in his mind, theology, could not withstand the pressure, and then the socialists couldn't, either. And so he's trying to figure out, what kind of conceptual world do we need to make it so that this cannot happen again?

When reflecting on the church's relationship to totalitarianism, Barthes put it this.

The church knows that all totalities of the world and society and also of the state are, actually false gods and therefore lies. In the end, you don't have to be afraid of lies. Lies don't have any legs to stand on. And in the church, one can know that whenever the church takes these lies seriously, then it is lost with all calmness and in all peace, it must treat them as lies. And the more that the church lives in all humility and knows that we, too, are only human, and there are also many lies in us. Then it will also know all the more surely that God sits in governance over and against the lies that are in us, and over and against the lies in the world and in the state. And in that case, the church, regardless of the circumstances and no matter how entangled and difficult the situation, remains at its task and knows itself to be forbidden to fear for its future. Its future is the Lord. He, not the totalitarian state, is coming to the church.

Jeffrey Root: Bonhoeffer meets Karl Barth during the Nazi resistance

So, Jeff, when you think of where Bonhoeffer is in this story, he gets back from New York and has had an ongoing relationship with Barth on the page, but is headed off to see him. For those who aren't familiar with Karl Barth, what is it that makes him so attracted to someone like Bonhoeffer that when he gets off the ship, he says, family, I'll see you in a little bit, because I'm going to make a pilgrimage to talk with a theologian.

I need to go see the guy who wrote epistle to the Romans, meaning Paul. No bard did a commentary on the Book of Romans. There were many editions of it printed, but the saying was that this was like a bombshell on the playground of the theologians was one of the expressions used. It is incandescent, even to the point of being hallucinatory. The way that Barthes takes a kind of existential kierkegaardian and God is the infinite qualitative distinction posed to humans. There's almost no contact between God and the human in the epistle to the Romans. But it is amazing for its revolutionary use of language, its biblical interpretations, its exegetical creativity, nothing like it had been written. It horrified people like von Harnack and other theologians who thought it was not in the scientific theology mode that they had been teaching and had been trained in. But Barth had come to understand that the Bible was not the right human words about God. It was God's revelation to humans. It was God's word addressed to humans. And so with that kind of shift in his thinking, he entered into, and we can even say maybe creator of the kind of theology of crisis that was reigning in german, swiss european circles in the 1920s, as that world also was trying to respond to the absolute devastation of World War one. Where is God in this? How do we find God in this? And Barthes moves from his pastorate in Sophonville into theological schools in Germany. And in 1931, he just happens to have taken a chair at the University of Bonn. And Bonhoeffer gets back from America, and he says, I want to go see that guy. And so he does.

Here's Andrew Root telling us the story of Bonhoeffer's visit with Barton when he.

Returns from New York City in 1930, in that school year of 30 to 31. He comes home that summer, and he's exhausted from his travels abroad. And his parents. He's the baby boy of the family. They try to shoo him off through their little retreat getaway, their little mountain house. They ask him to go get some rest, but he can't do it. He immediately goes and meets with Karl, Bart and Bon and starts that relationship that will become very important during the resistance. It'll be the first time he'll meet Karl Bartley. Karl Barth will be very suspicious of this young man from Berlin who's here. If you know the backstory of Barth, he has started a whole theological revolution, really, by opposing the theology, that's happening in Berlin. So for a Berlin PhD to show up in his class, he is very uneasy about it. But Karl Barth was known to be skeptical of people, but also to be easily converted with one good statement or question. And in the first class, Dietrich raises his hand. He calls on him. He makes a statement and asks a question about Luther. And Karl Barth is enamored, just loves him. And so they have dinner, and they really enjoy each other. And he becomes Dietrich's mentor. And particularly through the resistance is very important.

Andy Root calls to our attention the fact that Bonhoeffer had many mentors. We can look at Niebuhr, we can look at Lasserre. We can look at the people that he methadore at union. We can look at his friends. But Barth was very central to Bonhoeffer's life, and their lives would end up becoming entwined all the way down to Dietrich's last days in prison, when he was still aware of the work that Barth was doing in his newest edition of church dogmatics. Shortly after this exposure to the great man and Bonn, Bonhoeffer embarks on another trip that would significantly impact his life. It's an ecumenical conference being held at Cambridge, England. this conference would mark another step on his journey away from german nationalism and ethnocentric attitudes. But it's interesting how that whole trip came about. As Andy Root tells us, there's another.

Situation going on here where Dietrich has had to put off his ordination because he's gone too fast. At this time in that Senate, you had to be 24 to be ordained, and he has PhD in hand, and he has just simply gone too fast. Finally, by the summer of 31, he's old enough to be ordained, and he goes to his ordination supervisor and says, I'm ready to be ordained, but could I have a little time? I've just been invited to give lectures at the university. Could you give me a few more months? The person overseeing his ordination was a man by the name of Max Dissell. And Max was very cunning, very loving, good mentor, but very cunning. And he said, well, Dietrich, I don't know. We put this off for two years. You've been to Barcelona, you've been to New York City, all waiting out the clock for you to be ordained. I don't know if we can do this. But I tell you what, if you will go with me to Cambridge, England, there's a conference for the ecumenical movement. If you will go, then I think I can push this off for a few months. So he goes, and we don't know what happens there, but Dietrich goes as a guest and leaves as the secretary to youth in the ecumenical movement.

Hey, friends, I want to invite you to come with me and Andrew Root this June to Berlin, Germany, for the rise of Bonhoeffer travel learning experience. You'll be able to explore theology, culture, and faith through the lens and story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It will weave together an integrative mix of lectures, tours, conversation, experiential learning, and guess where our classroom is at Dietrich Bonhoeffer's very own home. So if you love thinking about his life, then consider joining us for this once in a lifetime opportunity perfectly constructed for anyone seeking to have a deep encounter with Bonhoeffer and wrestle with his piercing insights about faith for the modern world. We're going to explore these themes in Bonhoeffer's family home, visit various museums and sites, get to see his neighborhood, tell the story, and do it all in a small group of people, just the number of people that fit in the man's living room. So come join me, Andrew root, and it's going to be a good old time. For more information, head over to bonhoeffertrip.com. bonhoeffer trip with one p not, like my name.com. you're listening to the rise of Bonhoeffer. If you want to get to know even more about Dietrich's life, read a little bit of them, hear long interviews with these Bonhoeffer scholars throughout the series, and have live conversations and Q and A with Jeff and I. Then head over to riseofbonhofer.com and you can join up for our parallel online class. This class is donation based, including Xero so if you just want to dig a little bit deeper, nerd out a bit more about Dietrich, learn even more about his own struggle and the way he wrestled with his time in history.

Bonhoeffer's entrance into ecumenical circles raises suspicion among German theologians

Head over rise of bonhoeffer.com dot there's nothing more Bonhoeffer than being dragged to a conference and coming home with a new leadership responsibility that fits his personality so well. And yet these relationships formed at Cambridge in such a short time, just a week, invited him into the larger ecumenical movement. The work across different denominations within the life of the church, but more importantly here, across different national boundaries, boundaries that this time in Europe, the connection between individual nation states and their particular religious traditions is so tied out of world war one, leaders within each of these churches are going, how in the world do we have a world at war where christians are killing christians? Shouldn't there be something that binds us together, maybe our baptism, maybe the table, maybe our shared confessions of Christ as lord that can undermine the energies of nationalism and militarism? And there Bonhoeffer finds a community that shares this invitation to deep discipleship, disciples who are more attached to their lord than their nation and more attached to the way of the cross than maybe a gun.

It's true, for most humans, exposure to a wider circle of friends and acquaintances offers a more expansive horizon. Because the ecumenical movement was in its beginning stages, Bonhoeffer's entrance into those circles gives rise to suspicion among his theological colleagues. Back in Berlin, theologians must be mentioned, would take very, very different stances toward Hitler than the one that Bonhoeffer took. The question of where Bonhoeffer's true loyalties rested was discussed in certain circles. Is he german? Is hedgesthe committed to Germany? And Bonhoeffer's move into that ecumenical world of Christians from other countries was seen as a threat by theologians like Paul Althouse and Emanuel Hearst, who remained suspicious of any action that Bonhoeffer took that was seen as being subversive to the cause of german supremacy.

I think people listening need to know that this ecumenical connection plays a very important role when Bonhoeffer eventually becomes a part of the conspiracy and becomes a double agent of sorts, working to undermine the nazi government.

Because his exposure here starts and he ends with a leadership position. His profile rose in european organizations, european countries, as he established these relationships and networks that would become important. As Hitler rose to power, people in other parts of Europe would look to Bonhoeffer to ask him what the situation in Germany really was, as opposed to the propaganda that some of the german Christians were offering to european communities.

One of the things that made this possible are the kinds of friendships he made with Europeans in America. When we think of that experience and encounter with Lasserre, you can see how that friendship opened up for him. The potential that the connection to others and, other nations in the body of Christ can play a more central role for his own identity than perhaps the theologians at home that find his ecumenical commitment a bit suspicious.

And we're going to talk about the way that those relationships unfolded in future episodes.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer studied theology at Berlin University

But for now, let's think about the fact that back in Berlin, he's landed a position as chaplain at the technical school. He didn't find a receptive audience there. It was very difficult, and let's just be honest, whose students had absolutely no use for religion. He cobbled together a, ah, position at Berlin University, teaching scattered classes, and not to put too fine a point on it, was like being an adjunct hell in an american university. The fact of the matter is, is that Bonhoeffer was paid whatever the students themselves felt he was worth. So that's how sort of marginal his position was. So there he is, a, brilliant theologian, world traveler, two dissertations to his credit, and he's having a quarter life crisis trying to define what his life is going to look like. And he gathers little support from theological colleagues in Berlin who start to look at him going, what are you doing with all these other european people? So in February of 32, Bonhoeffer ends up moving into a working class neighborhood in northeast Berlin, where he took up the challenge of leading a comfort man class of 50 teenage boys suffering from testosterone poisoning. We'll let Andy root pick up the story from there.

Dietrich lives in the west side of Berlin, over in the Grenvald area, and a very leafy professors area. The kind of head of the Weimar Republic, if you think of the Weimar Republic after the war, this very kind of cultured republic that comes. It's this republic of artists and reflective people. The hub of that place is the very neighborhood that Dietrich is living in. But he gets a call that says, we have a confirmation class in weddingse, which is a district in Berlin on the east side, and it's a very communist district, a place where there is many challenges economically, especially in this period, as we are in a time of now. Hyperinflation, which it's hard for us to imagine. The utter hyperinflation that was going on. Other stories in Richard Evans three volume book about the rise of the Third Reich would say, you could go to a cafe and a cup of coffee could cost you 800 deutsche marks. If you were there too long, if you were there 2 hours and you went to pay, it could be 10,000. That the hyperinflation was just going at an incredible rate. And there was a lot of poverty in this area. And the National Socialists were known that when they went into an area, what the SA particularly would do would go to the communist area, and what they would do is start street fights. They would beat you up, and they would use the chaos of the street fights to then also pitched to the public that they could bring law and order. They were the ones who started the fights, but they could also stop the fights. So you should follow them. And of course, there's a lot of fear after the great war in what happened in 1917 in Russia with the Bolshevik takeover, there was a major fear that the communists could take power and the old money in Berlin, they wanted anything but that. So all these deals started to be made with the right, because they just didn't want the communists to come to power. Dietrich gets asked to take over a confirmation class. So this is at the Zion church in wedding in this communist area. There's a great book called I knew Dietrich Bonhoeffer. And it's about 20 people who write little pieces about their times knowing Dietrich Bonhoeffer. And we have two pieces in there from kids who were in this confirmation class and they say went to the confirmation class. All boys in this wedding district, many of them with black eyes, having been beaten up by SA stormtroopers. They come in, and it is an old pastor near retirement named Mahler, hasn't been able to control the class. They've been out of control. So he takes them into the education building, and the boys are all upstairs with a railing looking down. And as old pastor Mahler and Dietrich walk in, the boys start throwing banana peels and paper down on them. They get up to the top level, and the old pastor wrangles them into the room. And then he says, as they're all yelling and loud, he says, your new teacher is Herr Doctor Bonhefere. And then he leaves. He's, I'm out. I'm done. It's, all over for me. And all the boys start chanting, bomb. And Mahler's out of there. He's thinking they could kill him now. It's not my responsibility anymore. I'm done with this. And the story goes that Dietrich just listened to them chant bond. And then at about this volume, he started telling them a story. He started telling a story about his experience in Harlem. And just the boys in the front could hear it. And then they were quiet to hear the story. And then a cascading wave, it went back, and they were quiet. They heard the story. And he said, if you come back next week and will be quiet enough for me, I'll tell you another story. And it transformed his confirmation class, telling them these stories. He writes a letter to his friend Erwin Schutz, who he met in New York City. He said, for the first time ever in my ministry, I've had behavioral problems. But he said, what I just do is I come to the boys and I don't really even prepare. He does say, I'm Dietrich Bonhoeffer, so I know stuff. He said, I don't really prepare. I just tell the boys stories. And then I tell them the biblical story and I lace them together. And then he says, also I tell them apocalyptic stories. The boys seem to really like apocalyptic stories. Some things are universal, I think, here. And then he says, I think humorously, a little dark comedy here. He says, I think now my behavioral problems have been taken over and maybe I will avoid the fate of my predecessor, who the boys, quite literally, he says, aggravated their teacher to death. And it is true, poor pastor Mahler, about two weeks after giving the class up, had a heart attack and died. So you think your confirmation class is bad? They're still breathing. There's been worse ones.

Bonhoeffer moves across town to serve people affected by national socialism

So this is Dietrich Bon alfer at home, and it really changes him. And he does see Berlin in a different way, and he sees the challenges before Berlin in a different way, and he ends up moving in to wedding. It's part of the synod's process and confirmation that each confirman has to have a home visit. So Dietrich moves in and lives in this area and spends time with the boys and goes to each of the boys houses. It's a very different experience for this very rich, upwardly mobile young man to now be sitting with these folks. He realizes what's going on with national Socialism, what this means for his boys. And he sees poverty in a different way. And it really takes him to see otherness, I think, in a unique way.

Vicki Barnett observes Bonhoeffer's attentiveness to the different part of Berlin he's serving and how it gets expressed in his pastoral ministry and a special confirmation sermon.

Bonhoeffer understood the attraction. There's a sermon he gives to his students, I think it's in 1932, where he talks about their generation and how it's just been lost by the first world war and what has happened since then and the depression, and nobody has worked. And he describes his generation as being in freefall. And it's a striking image because that's how many young germans feel. And here comes Hitler, who's going to put everybody in uniform and put them back to work and offer them a vision of how Germany can revive itself. And so Bonhoeffer understands why that is tempting and the fact that he immediately says, but you got to watch out for this.

What's fascinating about his time with these youth and their families is that he just had to move across town. But in moving across town to the other side of Berlin, he leaves behind kind of an erudite upper middle class lifestyle with his family, a family that shares his political critique of the rise of the national socialist movement in Germany. And they aren't quite sure about his faith and, the level of intensity he has with it. And there across town, he encounters people in the working class, people who are experiencing the economic impact and are bearing the cultural shame of Germany in these intense ways. And those individuals whose families are increasingly attractive to national socialism. In that space, his faith comes alive in a new way. And I think it makes sense when you realize at the end of this story how Bonhoeffer resists having contempt for even those he cannot affirm. Ah, ethically, that is grounded in a time where he gets to know them in their material lives and in their relationships.

At this time, he's teaching the class. In 1932, Germany is teetering on the brink of collapse, and Bonhoeffer's place was to be a pastor to those on the margins of german society. At this point, in this setting, he found theological abstractions of little use. He was in a world of concrete reality, of Christ existing as community. And that community was all too visible in front of him. he also discovered that he was a gifted teacher. In many ways. He was also a teacher that was not meant for german academic society. He has this letter to Erwin Sutz, his friend from Union days, that he wrote from London. And he says, I, no longer believe in the university. In fact, I never really have believed in it. Much to your chagrin, here we have somebody then who has just decided he is going to live out this witness with those on the margins, those at the edges of society, those who are suffering. And he is going to, have a different kind of life. And it's interesting in this different kind of life that, he has a conversionary moment. It's very vague and kind of cryptic. Biographers refer to it Eberhard Betke his major biographer refers to it as the moving from theologian to a christian. But he has this moment in which the reality of the biblical text becomes very powerful. As he's immersed in this particular part of german society, he's immersed in this particular historical moment, one of many conversionary moments that he has. But in this moment, he finds himself moving once again from the theoretical to the real. And in this real, he embraces faith on a much stronger foundation than the one he had when he was thinking about it from an academic sense.

Jeff Bonhoeffer writes about the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1932

So Jeff Bonhoeffer is here getting little response in the classroom and engaging in his church work across class lines, across town. And he's seeing this growing tension in the life of the church, where they're struggling to make sense of what's going on politically and where their allegiance lies and what faithfulness looks like. For those of us that just don't sit around with the whole story of the nazi rise in our heads, could you let us know just what's going on here in the early thirties in the way it sets the context for the theological and political questions that are going to shape the next few years.

Of Bonhoeffer's life since the fall of 1932. Found Bonhoeffer, lecturing on the book of Genesis, becomes later on the book creation and fall. He's also giving these amazing Christology lectures. Around the same time, out on the streets, there are pitched battles between Hitler's brown shirts and socialism as Germany fell deeper into chaos. That tumult continues until, in a stupid and politically disastrous move, on January 30, 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as the new Reich chancellor.

After 14 years of violent struggle, Hitler has at last achieved the goal he set for himself as a tramp in Vienna. For Hindenburg, the ordeal is over. an aging general and a cynical opportunist have paved the way for Adolf Hitler to become the chancellor of Germany. Delirious stormtroopers march in the streets. The third Reich of Adolf Hitler is born. It will last, he says, a thousand years. On this night, Adolf Hitler has come to power, not as the result of any irresistible revolutionary or national movement, nor even of a political victory at the polls, but as part of a shoddy political deal. Hitler did not seize power. It was given to him through backstairs and trees.

Seeking to quell the violence, trying to appease the right, the political forces aligned with Hindenburg gave the henhouse keys to the fox. And in this, chickens just didn't come home to roost. The vultures did. And so you have a shift in german society, Hitler, being ever the manipulator, laid all of the chaos at the feet of the permissiveness of the Weimar Republic. It was their decadence, it was deviance, it was societal decay that had led to this particular moment in the german political system, in art and culture and lifestyle. All of the decadence had to be burned out. It was very purging, in a way, at that particular point then, Hitler was moving fast to consolidate power. What really helped him do that was the Reichstag fire, which happened on February 27, 1933. Hitler suspended the constitution, seized brawled powers to arrest dissidents. The first camp in Dachau outside of Munich is opened in March 22. It's also in March that Hitler pushed through the Enabling act, which gave Hitler and his cabinet almost total control of german political power. Less than two months after Hindenburg made that disastrous move, Hitler has consolidated unimaginable power. There, was a german word, the gleichscheltung, the aligning of all of german society into Hitler's desires. And one by one, institutions started falling into place. One of those institutions was the church.

Vicky Barnett: Between 1918 and 1933, Germany experienced intense church struggle

And at that point, I think it would help us if Vicky Barnett would explain the sort of situation that existed in Germany at this time, the period.

Between 1918 and 1933, that interwar period, between the end of the First World War and, the beginning of national socialism. You have these right wing, christo fascist movements across Europe, not just in Germany. There's one in Finland, there's one in Slovakia, there's one in Hungary, there's one in Poland. And it's fascinating to see how these movements, even before social media, on some level, they're interacting. The movement that takes off is the german christian faith movement.

So it might help to clarify what's at stake when Vicky Barnett is talking about the rise of the german christian faith movement. This is a particular segment of the protestant church in Germany. It would become known as the German Christians, and this would be the segment that would be most connected to, most approving of Hitler's aims, his goals, all the way down to the bunker. They wanted an authoritarian government to erase the decadence of the Weimar republic. This is one of the movements that's going to have a profound impact early on in 1933 when this church struggle begins. The German Christians, as we'll find out later on, were running into opposition of the confessing church. But for now, just wanted to focus you on the fact that the German Christian, the Deutsche Christian, were the group that was most in line with what Hitler wanted to do in Germany.

The german christian faith movement sort of comes out of various streams from the 1920s. And that's the movement that sort of starts the church struggle in 1933 because Hitler comes to power. The German Christians immediately pitch their wagon to the Nazis because they really support it. And when Hitler passes the aryan paragraph in April of 1933, which bars people of jewish descent from the civil service, the German Christians say, we need that in our church, too. So important clarification. This is one of those things that people often get wrong. The Nazis, when they implemented this law, didn't have the means to implement it across Germany in all of the different institutions. So the law is a civil service law, it's a federal law. They depend on institutions to conform. Some institutions do, some institutions don't. It takes a while for all of this to happen. It's within the protestant church. The German Christians say, we're going to pass a church law to do this, that move to pass a church law that conforms to the nazi law, but it's not the nazi government interfering in the church yet. It's saying, we're going to change our church to conform to this new state. That's what triggers the, german church struggle, because you get a debate about whether church can be changed in that way, what the implications are, what the theological implications are. And that's what directly leads to the emergence of the confessing church. And it's what Bonhoeffer writes about in April of 1933. They immediately get on the side of the Nazis and are sort of Hitler's fifth column within the church. That lasts for about a year and a half. There's so much tension within the church. It gets a lot of international attention. It turns out to be a liability for Adolf Hitler. So he backs away by late 1934 from the german Christians, although they're still very powerful in the 1933 church elections, they get positions in all of the different regional churches. They oversee most of the theological faculties, and they oversee most of the ordination committees. So that is what makes them a force all the way through. But that early, sharp, dramatic division that happens in 1933, that dies down. And so, you know, Bonhoeffer's story unfolds in the middle of this larger drama about way the church is going to go. Is it going to become a state church? Is it going to conform to Nazism? And those are the questions in that.

Early stage to set the stage at this moment of 1933 tumult.

Christo fascist church in Germany is making connections with other Christo fascist churches

We have a situation where we have a Christo fascist church that is making connections with other Christo fascist churches in Europe. And these churches all share similar ideas. I realize that the word fascist may be defined by the one who's defining it, but there are still some kind of family resemblances there.

And when it goes to christofascism, this is a concept that really emerges in the exploration and understanding of what happened to the church in Germany, where this particular group, the german Christians, are latching on to this vision of authoritarianism as a solution to the shame and challenges facing Germany. They level up the nationalism and militarism within the state. It grounds its fear and exclusion in rampant anti Semitism. And these kind of authoritarian gestures exist within the state and the church. There's a desire for a pure church, one's without any jewish blood involved in the church, its leadership in the baptismal waters, and they don't want any impurities in the state. And that exclusionary and intolerant picture is one that ultimately ends up perverting the teachings of Jesus. It compromises the integrity of the church. And yet the response it's getting in the german populace is one that Bonhoeffer recognizes as rampant idolatry. It resonates deeply with what we talked about at the beginning of the episode of Barthes, recognition that so often, if, we don't let God be God and tell us who God is in the cross dead Christ, we give to God our own image, our own desires, our own prejudice, our own desire for power and prestige and possessions. And we render, on the other, responsibility for anything that makes us uncomfortable, anything that's a challenge before us, anything that.

Generates fear in some ways because of his family, because of the situation in which his relatives, his brothers, his sister, father, mother, all the extended family lived, their opposition to the kind of authoritarianism that was emerging in Hitler's. The idea when he comes then to that radio address that we talked about earlier on de Fuhrer principle, we don't know why that address was cut off, regardless of what happened. Bonhoeffer kept on that theme after that radio address to try to warn Germany about the dangers of an authoritarian, very rigid hierarchical structure, about the leader who is going to be a misleader, who claims that only he can keep you safe, that only he can do the things that will protect you. This makes for a very powerful response to a german christian church who is increasingly aligning itself in all of its institutional structures with what Hitler wants to do.

I think people can understand how christians can look at the world and see these kind of economic disparities, seeing violence erupting, seeing challenges that are intergenerational, where you don't know what kind of future your children or grandchildren are going to have and say the church has to do something here. But what made so many scholars of this period identify this movement as christofascist is when the desire for God to act gets crystallized or made concrete in a political movement, and one that is inherently authoritarian, anti semitic. And it's one where the call to make one particular nation great again is put in bold and put in the voice of Goddesse.

Yeah, I just want to go ahead and say right here there's a great book called Twisted Cross, the german christian movement in the Third Reich, and it's by Doris Bergen, profound historian of these times. And she lays out those marks. One of the marks is that notion of the sacralization of the nation. And we talked about that earlier also with that kind of theology of providence, that if you have connected your culture to the demands of God, or to the commands of God or to your theology, then it's very hard to break away from that and understand that your theology or your culture may be flawed.

The arian paragraph found purchase in the original guidelines of the german christian movement

As we approach this issue of the arian paragraph, the argument of the confessing church is not going to be necessarily Jews as Jews, but what are we to do with the baptized Jews in our congregation? And should the state have a, say in whether or not they participate with us? At this point, the arian paragraph hits a little differently in certain segments of the church, but it really, really, really found purchase in the original guidelines of the german christian faith movement that was written in 1932. In this, we hear these words.

In the mission to the Jews, we see great danger to our people. It is at the point at which foreign blood enters into the body of our people. There is no justification for its existing alongside the foreign mission. We reject the mission to the Jews as long as Jews have citizenship, which brings with it the danger of race blurring and race bastardizing. Holy scripture speaks both of holy wrath and of self denying love. It is especially important to prohibit marriages between Germans and Jews. We want a protestant church with its roots in the people, and we reject the spirit of a, christian cosmopolitanism.

The german christian vision is one where the deeper the religious allegiance, the deeper the exclusion, the deeper the purity, and the deeper political power becomes the solution for the disciples. It's hard to hear that and not think of that passage from Barth. We heard earlier of the calling out of lies that come in the voice of culture, society and politics, and the call to radical commitment to the word of God in Christ. Challenging these lies, those different dispositions are hopeful for people wrestling with this historical period and in our own, what is it and where do we go to understand our identity in a complicated, anxious and difficult time? For some, you go to a church of increasing sameness and rigid ideology. And for others, you go to a God who shows up and shows up with condemnation for the lies that are orienting you, your fear towards the other in violent ways. And this God from the outside shows up in the face of the other. And it's that attentiveness to God, to Christ in the face of the other, that has moved Bonhoeffer all the way up to this point.

And now Bonhoeffer is going to have to struggle with the fact that the church he had hoped would also have that vision finds itself fragmented in the face of what Hitler is doing.

With the funeral of Hindenburg, the last vestige of restraint disappears. For Adolf Hitler, the last obstacle has finally been removed. His control of Germany is now absolute. Because order was valued more than honor. Adolf Hitler has had his way. A nation has become the tool of a tyrant.

We will see you next week for the rise of Bonhoeffer.